Uniting for Turtles in Chennai: Meet The Volunteers Who Sacrifice Nights to Save Olive Ridleys

“Identifying the turtle track amidst the stillness of the ocean provides me an adrenaline rush, which is almost similar to identifying a pug mark and tiger wrinkles during the safari.”

Every night, as the city winds down, a small group of dedicated volunteers of Students Sea Turtle Conservation Network (SSTCN) gathers on the shores of Chennai, flashlights in hand, scanning the sand for telltale signs of nesting turtles.

They come from diverse fields — marketing, consulting, environmental science, and more, wrapping up their day jobs only to spend their nights by the sea. Why? For the love of the Olive Ridley turtles.

Walking on the shores every day

Every turtle nesting season from January to May, the passionate volunteers from SSTCN come together for an exciting season.

“Every day, we have four volunteers, two on either side, walking the stretch from Neelangarai to Besant Nagar from 11 pm to 4 am,” shares Arun V., a coordinator at SSTCN.

Observing the mother turtle begin her nesting ritual is a surreal experience, which can be observed in three steps.

“She does her turtle dance called compacting to dig the nest. Then she goes into a trance when she lays the eggs to overcome the pain of labour,” explains Gopala Krishnan, a senior consultant at Cognizant.

“At this time, it is okay to go a little closer to the turtle. At the end, she dances again to close the nest. It is interesting to look at the effort it takes for the turtle to lay eggs,” Gopala describes, who has been volunteering for five years.

“Sometimes the volunteers get to see the live nesting, which takes about 45 to 50 minutes, while the other times, the turtle tracks become our guide to collect the eggs,” shares Raghuraman, a naturalist. “My first turtle walk was on the 29th of January, 2007, and around 2 am, I saw my first nesting turtle,” recalls Reghuraman.

The search for a nest begins by identifying turtle tracks — patterns in the sand that indicate a turtle has come ashore, but not every track leads to a nest.

“We identify an original nest from a fake trail with the presence of sand clearance that the turtle has done,” Gopala explains

“We start to clear the nest from the centre carefully using a metal probe, and at one point, you could feel how the probe goes into the sand much quicker and immediately than in the other places. The neck of the nest is filled with loose sand in comparison to the other parts,” Gopala adds.

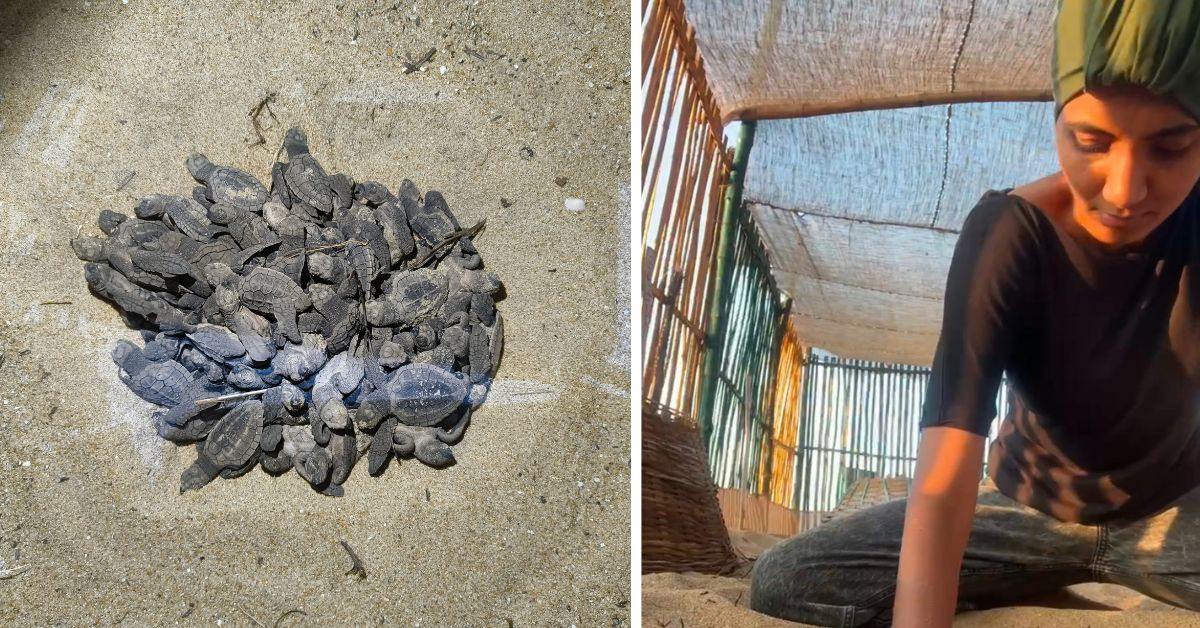

The Olive Ridley eggs have to be carefully transferred from the nest to the hatchery.

The Olive Ridley eggs have to be carefully transferred from the nest to the hatchery.

“Once the probe identifies the location, you dig a hole big enough for the arm to go in, and after digging for 20 cm or so, you will find the eggs underneath the sand layers. I can never forget the experience of picking up the eggs for the first time,” shares Gopala.

The eggs, round and the size of ping-pong balls, are carefully lifted from the nest and placed into a cloth bag for transportation. “It was shocking and fascinating to see the eggs being taken out,” Gopala says.

“It is an evolutionary trick by the turtle that the eggs are soft and flexible, so when they fall from the turtle to the deepest point of the nest, which is 30 to 40 meters, they do not break. They might slightly deform or get pressed initially, and after a few hours, they become hard.”

Public walks — a place of awareness

Every weekend, on Friday and Saturday nights, the public gets the opportunity to witness this phenomenon.

A mix of corporate professionals, school students, and conservation enthusiasts, anywhere between 30 to 50 people, come together for a unique experience — learning about and participating in the conservation of Olive Ridley turtles.

The walk begins around 11:30 pm when the group assembles. “One of our volunteers follows up with the registered participants, ensuring that those who are genuinely interested get a chance to join,” says Raghuraman.

The night starts with an hour and a half of a briefing session, during which the volunteers explain the purpose of the walk, the need for conservation, and the threats these turtles face. “Depending on the crowd, we conduct the session in English or Tamil, sometimes even splitting batches accordingly,” Raghuraman explains.

During the discussion, participants also get an overview of various environmental issues, both local and global, broadening their understanding of conservation. Then, the real walk begins. The volunteers lead the group along the shore, scanning the sand for signs of a nest.

“If we find a nest, we show it to the participants and explain how we locate one, how we track the turtles, and the whole process of nest identification,” Raghuraman shares.

While many would love to be part of this experience, SSTCN is mindful of the turtles’ well-being. “This year, we conducted more than 50 walks, but there were hundreds of requests. However, we had to restrict participation to 60 people per walk because, at the end of the day, our priority is the turtles. If our actions disturb them, then there’s no point in doing all this,” says Raghuraman.

The volunteers work swiftly to relocate the eggs to the hatchery. “It is also important to transport them to the hatchery before they become hard to avoid the chances of breaking the eggs,” he notes.

Carefully cradling the fragile eggs, the volunteers continue their walk along the shore, ensuring that each clutch reaches a safe incubation site, away from natural and human threats.

Hatchery duty — a separate world

The hatchery is where the conservation efforts come full circle, ensuring that the Olive Ridley hatchlings have the best chance of survival before they make their way to the ocean.

As Nishfa Sherin explains, one of the most rewarding aspects of working in the hatchery is the diversity of people involved — from school kids and part-time volunteers to full-time conservationists and even the Tamil Nadu Forest Department.

While the turtle walk takes around eight hours, the hatchery demands 24/4 monitoring.

While the turtle walk takes around eight hours, the hatchery demands 24/4 monitoring.

“The main thing about the hatchery is that we have to keep monitoring it 24/7,” shares Raghuraman, since they tend to emerge anytime.

“They have to be released quickly during daytime as the temperature goes up from 35 to 38 degrees, making it very hot for the young hatchling, which is hardly 3 centimetres in size,” Raghuraman adds; otherwise, they will be roasted in the sun and die.

“You get to see people from different walks of life working for the same cause,” she says. Each evening, after finishing her office work, she heads to the hatchery, where responsibilities are divided among volunteers.

The first task is documentation, manually recording data in logbooks and now also in an exclusive Tamil Nadu government app introduced this year.

The dead shells has to be removed to keep ants and other insects away from the nest.

The dead shells has to be removed to keep ants and other insects away from the nest.

Volunteers check how many nests are due for hatching and manually inspect them to see if any hatchlings are ready to emerge. The second task is to identify overdue nests where hatchlings might be struggling.

“If a nest was due yesterday or the day before and we don’t see any activity, then it is time for us to excavate and take them out ourselves,” Nishfa explains.

Sometimes, hatchlings get entangled in roots, making it difficult for them to emerge, or they become dehydrated. Senior volunteers carefully excavate these nests, retrieving the remaining hatchlings while also documenting unhatched, sterile, or dead eggs.

This process ensures that as many hatchlings as possible make it safely to the sea, giving them the best start in their journey ahead.

The joy of releasing the hatchlings

Every evening between 6 and 7 pm, a crowd gathers to witness this mesmerising event: the public hatchling release. “It is important to create awareness, as that’s the only opportunity that we have to reach the public in large numbers,” says Nishfa.

The growing popularity of these releases has made crowd control a challenge. “From last year, the crowd has been quite too much,” Nishfa notes.

To manage this, volunteers set up bamboo barricades, dig them into the sand, and rake the area to clear dustbins and other debris, ensuring a clean and safe release site.

Once the public is seated or standing behind the barricades, a volunteer briefs them about SSTCN’s conservation efforts. Strict rules are enforced: no flash photography, no touching the hatchlings, and minimal noise.

“We request them not to take any photographs or use flashlights,” Nishfa shares. However, some still break the rules in their excitement, and volunteers must repeatedly intervene.

Then comes the most surreal moment, watching the hatchlings make their way to the ocean. Volunteers guide them with torchlights, as baby turtles instinctively follow the brightest source of

light. Alongside this, another challenge awaits, which is protecting the hatchlings from predators.

“While we release, there are these crab holes,” Nishfa explains. “So as part of the raking, we shut all the crab holes. Because suddenly there will be a crab popping up in there and will take the little hatchlings and run away,” Nishfa adds.

The tiny hatchlings have to be guided by a light source to enter the ocean safely.

The tiny hatchlings have to be guided by a light source to enter the ocean safely.

Even after the turtles disappear into the waves, the work isn’t over. Volunteers patrol the shore for about a hundred meters in both directions, making sure the hatchlings don’t get washed back.

The process then repeats for the next batch, but this time, without the public. “Late in the night, when the temperature is cooler, the hatchlings will be emerging a lot. And to witness this there will be just two volunteers. Seeing 300 hatchings going into the oceans is a special moment,” adds Raghuram.

Finally, volunteers return to the hatchery, clear out eggshell waste, and dump it in a designated pit far from the site — wrapping up another cycle in their ongoing mission to safeguard these vulnerable creatures.

What does it take to become a volunteer?

Becoming a volunteer at SSTCN requires more than just enthusiasm; it demands passion, commitment, and love towards conservation. Volunteers must be mindful that human intervention has made survival even harder for these turtles. “You can’t do this just for college credit,” says Gopala, highlighting that genuine interest is key.

The work is demanding, stretching from 11 pm to 7 am, making it essential for volunteers to balance their personal and professional lives while staying committed to the cause.

Walking along the beach at night also requires courage, as Gopala himself recalls facing harassment from a drunk man.

Volunteers at SSTCN are doing this out of passion, not for fame.

Volunteers at SSTCN are doing this out of passion, not for fame.

“It is a shame,” he adds, acknowledging that safety concerns have limited female participation in daily turtle walks. Moreover, this work isn’t for those seeking recognition. “If you are doing this for appreciation, this is not your cup of tea,” Arun shares. Yet, they continue steadfastly, fueled by their love for the turtles.

“I hope that one day my kids get inspired to be involved in turtle conservation,” shares Gopala, reflecting the deep sense of responsibility and legacy that fuels their work.

Edited by Leila Badyari Castelino; All images courtesy SSTCN volunteers

News