What are Farmers Growing Under Solar Panels in Their Farms? Understanding Agrivoltaics

In Maharashtra’s Parbhani, hope takes form in a unique dimension — 5 acres, to be precise. This is how tall the smattering of elevated solar panels here is; beneath them, ginger, turmeric, green gram, and okra (lady’s finger) sprout. Govind Rasave (25), the farm manager manning the agrivoltaic setup (a system where crops are grown beneath elevated solar panels), is looking forward to the bountiful harvest.

Govind enjoys his front-row seat to this mini revolution taking off in real time. The Parbhani setup — part of a 50 MW Renew Power solar installation by SunSeed APV, Kanoda Energy, and GIZ German Development Cooperation — is one of the few pilot projects paving the way for an agrisolar boom in India. While the concept has found success internationally, it is still nascent here. Adapting technology to diverse agricultural settings has proven tough.

But now, with a sizable number of pilot projects across the Indian hinterland, solar entrepreneurs find themselves at the precipice of possibility. Govind vouches for this. In the two and a half years that he’s watched the Parbhani project bloom, he’s been in awe. “I live in the Zari village nearby, where I do sugarcane and cotton farming,” Govind explains.

The agrivoltaics setup in Parbhani involves crops being grown under elevated solar panels to maximise the potential of the land. Picture source: Vivek Saraf

The agrivoltaics setup in Parbhani involves crops being grown under elevated solar panels to maximise the potential of the land. Picture source: Vivek Saraf

The reason the Parbhani model does not include the same crop choice, he says, is because “these [the panels in Parbhani] are elevated solar panels. We haven’t experimented with growing sugarcane under the panels because of the height of the crop.”

Govind’s favourite part of his morning routine is assessing the land’s performance. Each day, it leaves him pleasantly surprised. “I check the crops and the panels to see whether the plants need irrigation, whether the soil is healthy, and how the setup is performing. It is exceeding our expectations. The best part is that the yield we are getting from here is comparable to what we are getting from our own fields.”

Horticulture crops grow well in agrivoltaic setups as the crops can borrow support from the structure. Picture source: Vivek Saraf

Horticulture crops grow well in agrivoltaic setups as the crops can borrow support from the structure. Picture source: Vivek Saraf

The farmer’s take is coloured by possibility. It highlights agrivoltaics as a potential catalyst that could help blend farming with India’s vision of expanding her solar footprint. But Govind’s optimism is contested by the apprehension expressed by other farmers across India. To them, agrivoltaics is akin to “losing their land to solar”.

Experts urge that a myopic view will unnerve farmers. Instead, they suggest viewing agrivoltaics through a bifocal lens, where the long-term advantages will outpace the short-term hiccups.

Can agrivoltaics break new ground in India?

India ranks fifth globally in installed solar capacity. The daylight hours, compounded by its geographical disposition, make harvesting the sun’s power a smart bet. But that being said, if India has to meet its goal of achieving 500 GW of renewable capacity by 2030 — with a current installed solar capacity of 100.33 GW — it will need to amp up its solar deployment.

The solution lies in the 75,000 square kilometres of India’s landmass — viable ground for solar generation. Farmers, however, are worried that their verdant sprawls of farmland will be rendered useless following the installation of solar panels, which will occupy a significant portion of the land.

The agrivoltaic pilot project in Nashik by Sahyadri Farms is exploring the potential of this new medium of blending agriculture with solar power. Picture source: Sahyadri Farms

The agrivoltaic pilot project in Nashik by Sahyadri Farms is exploring the potential of this new medium of blending agriculture with solar power. Picture source: Sahyadri Farms

If only there were a way to tie in solar energy generation with agriculture. Enter agrivolatics!

As opposed to ground‐mounted solar photovoltaic (PV) systems, agrivoltaics permits a co-location of solar and agriculture on the same land. The elevated panels ensure a dual vantage; crops can be cultivated on the land beneath the panels while solar energy generated from these panels can be used to electrify villages.

A pilot project stands in Nashik, Maharashtra, launched by Sahyadri Farms, one of India’s largest farmer producer organisations.

Programme Director Mahesh Shelke spotlights the potential of this one-acre plot of land powered by 250 kW bi-facial panels elevated at a height of 3.75 metres. Elaborating on the benefits, he says, “The dual use of land helps farmers earn through rent. In addition, the structures used in agrivoltaics make them a good support for horticulture crops like grapes. Instead of the farmer investing in a support structure, it is readily available.”

Through its research and testing, Sahyadri Farms is keen on tapping into the benefits of agrivoltaics and using viable agricultural land to harvest the power of the Sun. Picture source: Sahyadri Farms

Through its research and testing, Sahyadri Farms is keen on tapping into the benefits of agrivoltaics and using viable agricultural land to harvest the power of the Sun. Picture source: Sahyadri Farms

Reasoning their foray into agrivoltaics, Mahesh shares, “In rural areas, availability of energy is a problem — quality as well as quantity. Even when electricity is available, the voltage is low. Initially, we were thinking of microgrids for energy generation. But homes in villages are small; their roofs span a smaller area. So, energy generated by the panels might be insufficient.”

Agrivoltaics, he notes, is the most optimal solution, which will provide farmers not just with electricity and shelter for crops but also diversified revenue sources. It’s also lucrative for cattle, proven by the 2.5 MW solar plant, spread over 3.4 acres of land in Issapur, on the outskirts of Delhi.

Solar grazing — when the space under an agrivoltaic setup is used to grow livestock feed on which cattle can be reared — will open up multiple avenues for farmers to earn. Through its limitless possibilities, agrivoltaics is beckoning us to reimagine the food-energy-water nexus.

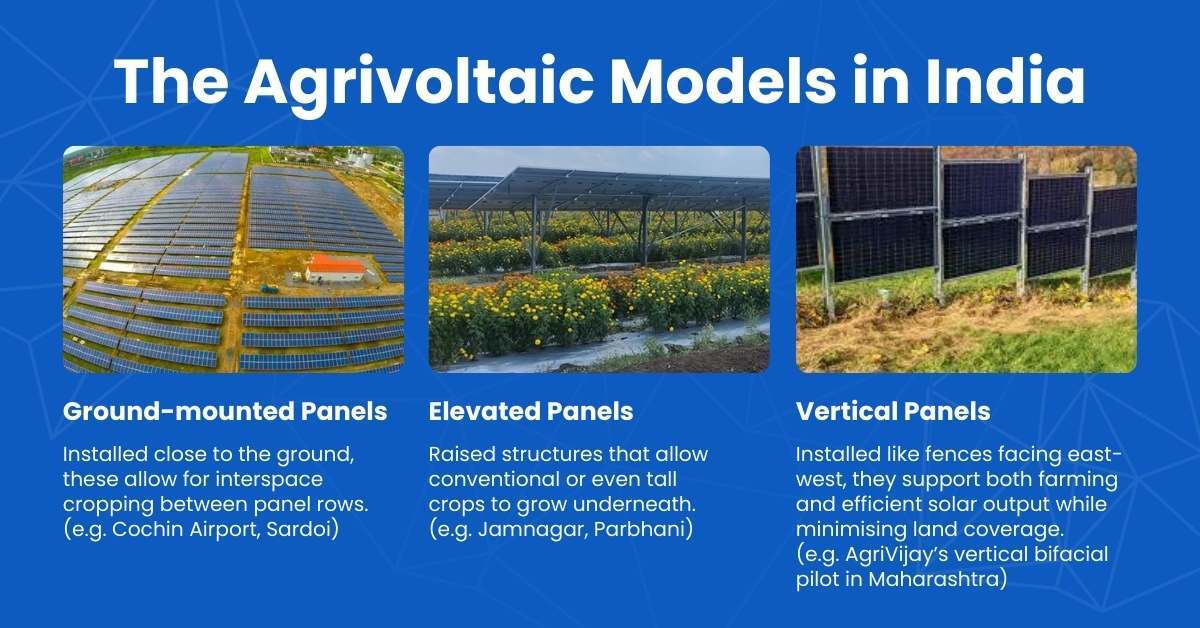

The different models of agrivoltaics in India

The different models of agrivoltaics in India

Among the many models, ground-mounted panels allow interspace farming. One example is the agrivoltaic site at Cochin airport, which is the most advanced of its kind in India; the other is a plant in Sardoi, Gujarat, where water used for cleansing is channelled to irrigate the interspace cropping area. Planted henna (Egyptian privet) further protects the setup from speedy winds.

The Cochin International Airport is an exemplary model of how agrivoltaics can be used as ground-mounted solar panels

The Cochin International Airport is an exemplary model of how agrivoltaics can be used as ground-mounted solar panels

Meanwhile, the CAZRI (Central Arid Zone Research Institute) research site in Jodhpur and the plant at Sikka in the Jamnagar district of Gujarat feature slightly elevated panels. Under the three-metre-high panels in Jamnagar, lady fingers, calabash (bottle gourd), coriander, and cluster beans can be grown, as can winter crops like tomatoes, cucumbers, zucchinis, and chillies.

The third model stretches its scope by increasing the panel height. The APV plant at Parbhani is an excellent example of this. The startling results of agrivoltaics heighten the need for public and private entities to buy into the system.

Reasoning why farmers shouldn’t view agrivoltaics as a “risky affair”, Vivek Saraf, founder of SunSeed APV, part of the team that launched the Parbhani project, says, “The risk is all ours. Farmers are stakeholders in agrivoltaic projects. The goal is to ensure that they get a better income than they did earlier, but without the risk.”

Breaking down the nuances of the model, Vivek says, “A farmer typically growing a staple crop earns a maximum of Rs 50,000 per acre per year. In agrivoltaics, he can earn Rs 50,000 just as the lease for the land. So, I’m not asking him to sell the land. He can even choose to work on this farm and earn money. In the process, the farmer has doubled his income.”

Farmers can earn more by leasing out their land to organisations interested in venturing into agrivoltaics. Picture source: Vivek Saraf

Farmers can earn more by leasing out their land to organisations interested in venturing into agrivoltaics. Picture source: Vivek Saraf

Vimal Panjwani of AgriVijay concedes. Farmers mustn’t be anxious, he weighs in. One of India’s first marketplaces of renewable energy products for farmers and rural households, AgriVijay’s success lies in having irrigated 500 acres of land through solar. Vimal points out how the model could be a buffer for financial distress that many farmers otherwise find themselves grappling with.

“Farmers find it tough to believe in the advantages of agrivoltaics, because it is something they cannot see yet,” Vimal weighs in. “Understandably, individual farmers will always be anxious about installing these projects on their farms, but when a group of farmers comes together as an organisation and installs a solar farm, they will be able to reduce their electricity expenses.” Only once farmers see the benefits in real time will it elicit a tacit acceptance of the model.

Vimal illustrates how farmers can capitalise on this: “Let’s say farmers are currently buying electricity at Rs 8 or 9 per unit. Once they install agrivoltaics, electricity will be sold to them for Rs 5, which is cheaper. This way, they are minimising their expenditure and reducing their dependency on the grid.” For farmers who are still apprehensive about the model going against the grain, Vimal has another solution.

AgriVijay has launched India’s first ‘Vertical Bifacial Solar AgriVoltaics Project’ in collaboration with Next2Sun and Wattkraft, in Maharashtra. “Our innovative Agri-PV system is designed to simultaneously support solar energy production and agriculture, maintaining over 90 percent land usability for farming.”

He adds, “This approach not only optimises land use but also ensures soil preservation, garnering substantial public support. By seamlessly integrating energy generation with agricultural operations, the Next2Sun solution exemplifies efficient and sustainable land management.”

The report Agrivoltaics in India: Fertile Ground? from the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA), authored by Dr Charles Worringham — a notable name in the space of green energy who has been closely tracking India’s energy transition — supports the vertical setup idea. When mounted vertically, like fences facing east and west, they produce peak power in the morning and afternoon, unlike horizontal panels that peak at midday.

“This configuration can help the grid by producing power closer to peak demand time, which is typically in the evening. This might allow certain loads like residential cooling to be brought forward a little and use that power directly, or by shortening the time between generation and use, make battery storage easier and more flexible,” says Worringham.

By bending the formula, the vertical set-up will solve all of a farmer’s anxieties about the land being occupied, Vimal is sure.

Through a climate-controlled approach, the microclimate of the plants grown in an agrivoltaic setup can be improved, thus scaling the success of the model. Picture source: Vivek Saraf

Through a climate-controlled approach, the microclimate of the plants grown in an agrivoltaic setup can be improved, thus scaling the success of the model. Picture source: Vivek Saraf

Even in mainstream projects, the specifics can be tweaked, Vivek points out, to achieve optimum results. “We’re currently working around a climate-controlled approach to agrivoltaics, which will enable the crops to take advantage of the reduced temperatures, as the panels will block out the direct heat they are exposed to.”

He adds, “In India, a lot of the crop productivity is lost because of excess heat. In climate-controlled cultivation, we’re improving the microclimate for the crop.”

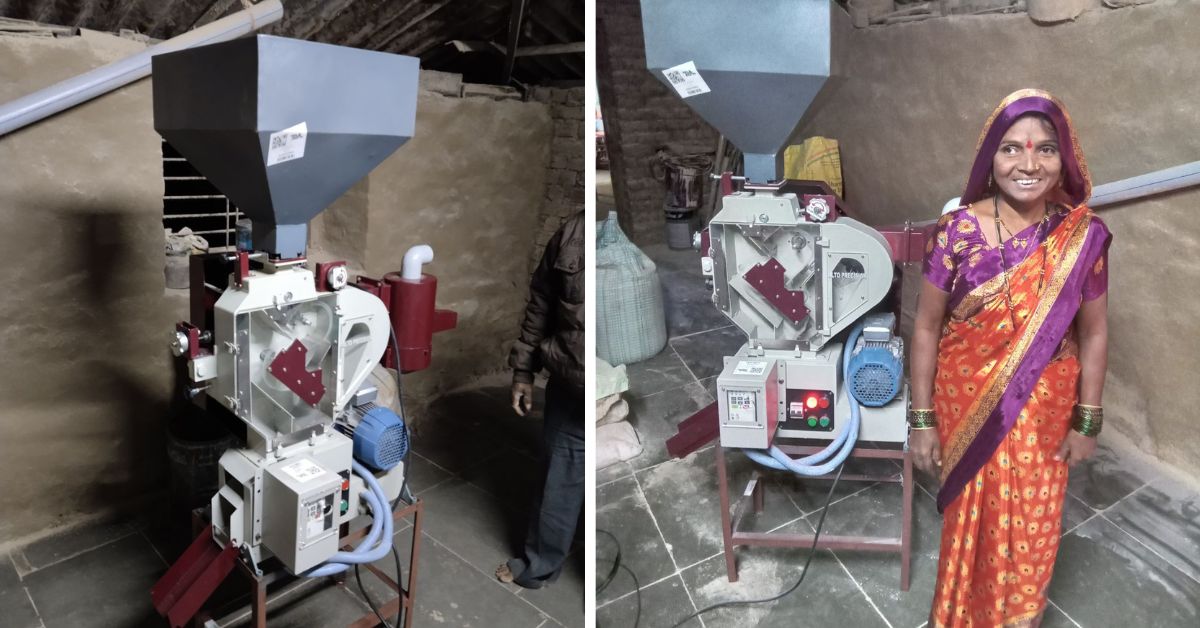

The rice de-husking machine distributed by AgriVijay to communities in India’s hinterland has proved a boon. Picture source: Vimal Panjwani

The rice de-husking machine distributed by AgriVijay to communities in India’s hinterland has proved a boon. Picture source: Vimal Panjwani

While transitioning farming models in India to agrivoltaics proves to be a mammoth exercise, these pilot projects underscore their outstanding viability. Vimal points to the solar rice mills they have distributed in remote tribal regions of Maharashtra that synergise with their ethos of familiarising communities with the benefits of agrivoltaics. These and many other developments are paving the way for the agri-solar revolution.

Is agrivoltaics the way forward? Put on your bifocal lenses, experts say. It definitely is.

Edited by Khushi Arora

Sources

News