Can Ancient Indian Stepwells Teach Us How to Solve Today’s Water Crisis?

India has a long history of living in sync with its environment, especially when it comes to managing water. Long before modern infrastructure, ancient Indian cities built systems that not only conserved water but also brought communities together. These weren’t just engineering marvels, they were public spaces, cultural landmarks, and symbols of resilience.

From the urban planning of Mohenjo-daro to the intricate stepwells of Gujarat and Rajasthan, here’s how ancient India mastered water management — and what we can still learn from it today.

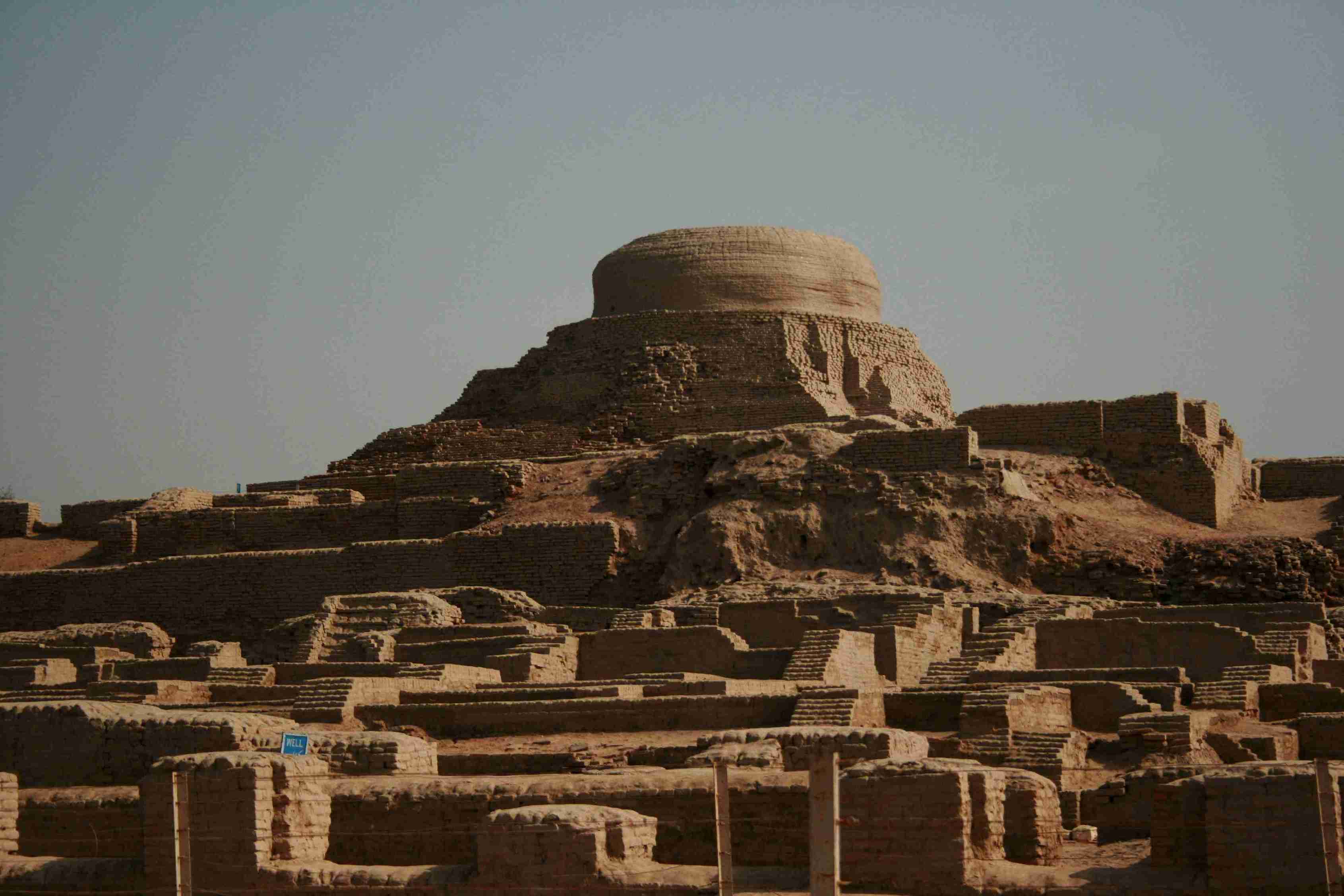

Mohenjo-daro: Urban planning ahead of its time

Dating back to around 2500 BCE, the Indus Valley city of Mohenjo-daro featured a level of urban planning that remains impressive even today. The city had a well-laid-out drainage system, private wells, and public baths — highlighting how central water was to everyday life.

With a well-laid-out drainage system, private wells, and public baths, Mohenjo-daro’s urban planning remains impressive even today.

With a well-laid-out drainage system, private wells, and public baths, Mohenjo-daro’s urban planning remains impressive even today.

Each home had a bathing area linked to a covered drain, which connected to a larger street-level drainage system. This reflects a deep understanding of hygiene, public health, and thoughtful urban design.

Chand Baori: Rajasthan’s geometric wonder

In the dry desert region of Rajasthan, stepwells served as both water storage systems and cool retreats. Among the most iconic is Chand Baori in Abhaneri, built around the eighth or ninth century.

Rajasthan’s Chand Baori helped harvest water while facilitating a shaded and cooler environment.

Rajasthan’s Chand Baori helped harvest water while facilitating a shaded and cooler environment.

With its 3,500 symmetrical steps across 13 levels, the structure not only harvested water but also provided a shaded, cooler environment — several degrees lower than the surface temperature. It was also a social space, where communities gathered to escape the heat and connect.

Rani ki Vav: Where engineering meets art

Built in the 11th century in Patan, Gujarat, Rani ki Vav is a stunning example of functional design that doubles as art. Commissioned by Queen Udayamati in memory of King Bhima I, this UNESCO World Heritage Site features over 500 intricate carvings of Hindu deities.

The artistic and functional design of Rani ki Vav helped replenish groundwater. Picture source: Shoestring Travel

The artistic and functional design of Rani ki Vav helped replenish groundwater. Picture source: Shoestring Travel

Beyond its beauty, the stepwell stored water and helped replenish groundwater, playing a vital ecological role while celebrating craftsmanship and culture.

Temple tanks: Sacred and sustainable

In southern temple towns like Madurai and Kanchipuram, large temple tanks — known as pushkarinis or kunds — were an integral part of both spiritual and daily life.

These tanks served ritual purposes, but they were also practical water reservoirs, collecting rainwater and helping recharge groundwater. The tank within Madurai’s Meenakshi Temple, for instance, remains central not just to the temple’s ceremonies but also to the city’s water management.

Blending culture with conservation

What made these water systems remarkable was how seamlessly they were woven into everyday life. Stepwells, tanks, and reservoirs were often gathering places, especially for women. They hosted festivals, rituals, and community interactions.

Built in the 1740s, Toorji Ka Jhalra is a stunning stepwell in Jodhpur that once served as a vital water source.

Built in the 1740s, Toorji Ka Jhalra is a stunning stepwell in Jodhpur that once served as a vital water source.

Many were funded by royals or wealthy patrons — not just as acts of charity but as lasting contributions to the well-being of the public. Their presence reflected a shared responsibility towards natural resources.

Decline and modern revival

Over time, especially with colonial infrastructure and modern plumbing systems, many traditional water structures were abandoned or neglected. But in recent years, there’s been a growing movement to restore and protect them.

From heritage conservationists to urban planners, many are turning to these time-tested systems for answers to today’s water crises, especially in drought-prone areas.

What we can learn today

Ancient India’s water management wasn’t just technically advanced — it was community-driven, climate-responsive, and culturally rooted.

As cities across the country face water shortages and overdependence on centralised systems, these age-old techniques offer sustainable, low-cost solutions that still hold relevance. By understanding and reviving these practices, we’re not just honouring our past — we’re investing in a smarter, more resilient future.

Edited by Khushi Arora

News