Widowed by Tigers, 500 Sundarbans Women Rebuilt Their Lives With 1 Woman’s Help & Fish Farming

‘Daredevils’ is how one could describe the men of the Sundarbans. They wade through marshy, murky waters teeming with crocodiles, snakes, and pneumatophores (the spiky roots of the mangroves) — the Sundarbans are one of the world’s largest mangrove forests, spanning an area of 10,277 sq km — to fetch a coveted prize, which in this part of the world is honey.

The sticky elixir is their main source of livelihood, contributing to a major portion of the global demand.

But, while one eye is on the water, the other constantly scans the swamp bank. In the delta, a pair of green eyes and a flash of yellow and black equates to a death sentence. And the locals have taken it upon themselves to forewarn visitors; Mumbai native Neeti Goel (48) was no exception. In 2022, during her first trip to the archipelago, she was stunned to hear that the tiger widow population (women whose husbands were killed by tigers) stood at over 3,000.

The honey gatherers wade through marshy waters in order to collect honey from the intertidal zones of the Sundarbans

The honey gatherers wade through marshy waters in order to collect honey from the intertidal zones of the Sundarbans

“Why do you still go into the jungles if you know there are tigers there?” she asked.

“How else can we collect the honey? If we don’t sell honey, we won’t earn. Either the tiger will kill us or hunger will.” The statement stayed with her.

The beast that parades the waters

Picture an expanse of land with a pretty interplay of rivers and mangrove forests, visited by over 260 bird species, dolphins, and river terrapins. Elsewhere in the world, a horizon like this one would probably invite exploration, but in the Sundarbans, another story is unfolding. In 2010, Chiranjib, a project officer with WWF-India’s Sundarbans team, was sailing near Phiri Khali in the buffer zone of the Sundarbans Tiger Reserve when he first spotted a tiger — but not any ordinary one.

This one’s disposition seemed at odds with its surroundings. “It was swimming fast, much faster than I have seen any human swim,” Chiranjib recounted in a WWF report. A deeper dive into the tiger’s ecological adaptations points to its webbed toes, which act as natural paddles, catapulting the animal to the island which is home to the tribes.

The tigers of the Sundarbans have adapted their bodies to swimming large distances due to the environs of the land

The tigers of the Sundarbans have adapted their bodies to swimming large distances due to the environs of the land

In the Sundarbans, the dark brings with it worry for the safety of the moulis (honey gatherers) who haven’t returned home. If they don’t return for a day, they are presumed dead. These losses have always felt personal to Neeti, who continues to be intrigued by how the tigers in the area have evolved into man-eaters. The answer lies in the River Ganga. “Before the dam was constructed on the River Ganga, dead bodies would float with the water and would be eaten by the tigers. They developed a taste for human flesh. Now that the dam has been built, the bodies do not float to the other side, and so, the tigers, in their search for flesh, reach the islands.”

The most dangerous of places is the intertidal forests, deemed out of bounds by the forest department — even the government compensation of Rs 5,00,000 excludes this region — as this is where the beasts lurk. But for the tribes in the delta, death is just the beginning of their troubles.

Tiger scientist M A Aziz, PhD, who teaches zoology at Jahangirnagar University and has been working for three decades in the Sundarbans, underscored the mental health impact that these attacks have on the population. The most common concern among the bagh-bidhobas (tiger widows) is PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder), with 72 percent of cases associated with tiger attacks.

Neeti Goel has been empowering the tiger widows of the Sundarbans through fish farming

Neeti Goel has been empowering the tiger widows of the Sundarbans through fish farming

Including the islands that complement and border the reserve, the Sundarbans cover an area six times larger than Greater London. And data collected between 2008 and 2022 suggests there were 275 tiger attacks on humans and 349 tiger attacks on livestock. “When an earning member survives a tiger attack or dies due to the attack, there is a big burden on the other family members. They suffer financially, emotionally, and socially,” Aziz points out.

Neeti agrees. Having worked closely with these widows, she has watched their existence become objectified following their husbands’ death. Providing them with money and food would be a temporary antidote, and so, Neeti zeroed in on fish farming as a means of empowerment.

Creating entrepreneurs in the labyrinths of the delta

Souravi Mandal (50) takes every visitor to the pond in front of her home. This is her pride and also the thing that feeds the family. In 2007, Souravi believed her life was over. She’d lost her husband and son to a tiger attack and her daughter to a crocodile attack. Souravi felt helpless. But today, every trace of worry is gone. She declares proudly that she is earning Rs 150 a day through fish farming. She is one of the 499 success stories that Neeti has scripted in the delta.

When Neeti started working with the communities of the Sundarbans, she wanted to hand-hold them, not spoon-feed them. “If you want to earn through fish farming, we can help you. But you will have to dig the pond in front of your homes,” she instructed them.

While bringing 3,000 women (the estimated number of tiger widows in the delta) wasn’t possible, Neeti decided to test the model with 100 women. “Our selection criteria were the extent of their loss and their needs,” she explains. Through the next four months, she watched fascinated as the women dug ponds, learnt how to make oxygen pipes using bamboo, put these into the ponds, and became well-versed in overseeing the fish entrusted to their care.

The women of the Sundarbans are earning enough form fish farming and goat rearing to sustain themselves and their families

The women of the Sundarbans are earning enough form fish farming and goat rearing to sustain themselves and their families

In four months, the fish population had multiplied “phenomenally”. Today, these feature in delicacies prepared at the five-star hotels in the Sundarbans. Aside from equipping the women with a financial agency, the model has given them a “twinkle in their eye”, says Neeti. “They began to earn through fish farming and have developed self-respect. In some cases, their families even took them back home,” she says. This feminist reclamation thrills her.

Cycles, food, e-rickshaws: Helping women tap into their potential

Neeti’s passions are divided between the headland and the hinterland. She’s the brains behind Mumbai’s ‘Keiba’, ‘Osstaad’, ‘Madras Diaries’, ‘Madras Express’ and Alibaug’s staycation brand ‘Amore Stays’, while her philanthropic arm extends across the villages of India. Spotting a couple of street children eating mud during the COVID-induced lockdown brought her face-to-face with the harsh reality of things.

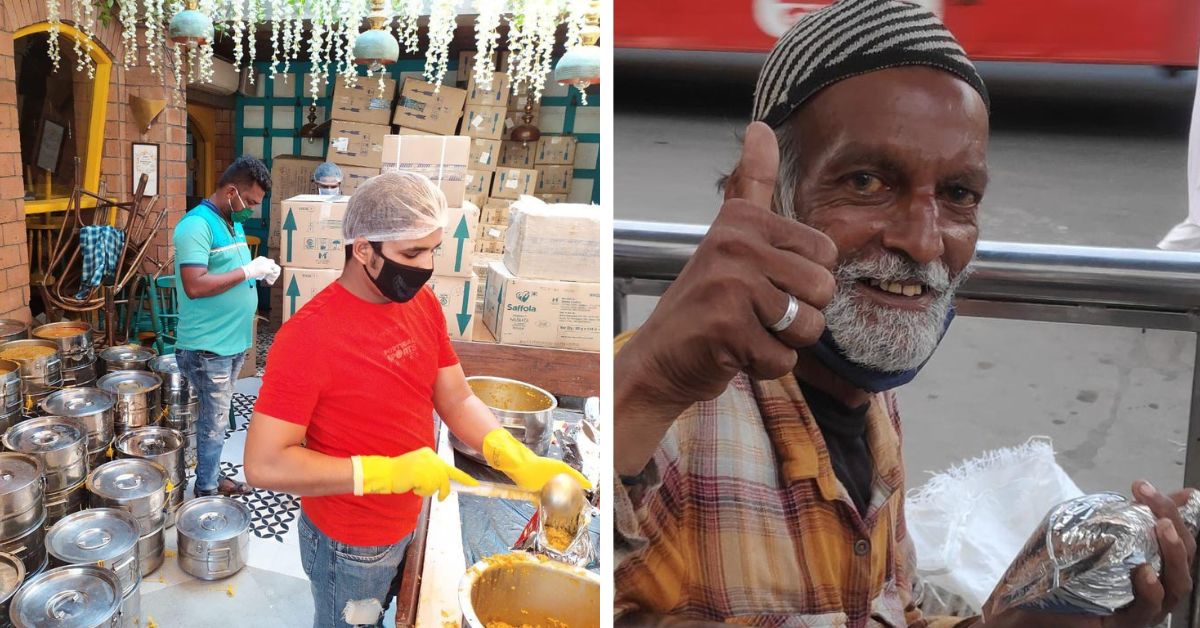

Through Khaanachiye 80 lakh meals were distributed to labourers and the poor during the lockdown

Through Khaanachiye 80 lakh meals were distributed to labourers and the poor during the lockdown

It also prompted her ‘Khaanachiye’ endeavour, through which 80 lakh meals were distributed to the poor and migrant workers during the pandemic. Alongside this, she also adopted 32 orphanages and 800 sex workers and helped rebuild 1,000 homes in Raigad, whose roofs had been displaced by Cyclone Nisarga.

The girls living in Naxalite-affected areas of Mirzapur were provided with cycles in order to make their way to school

The girls living in Naxalite-affected areas of Mirzapur were provided with cycles in order to make their way to school

It was around this time that she was made aware of how school-going girls’ education in Mirzapur was being curtailed because of Naxalite activity in their village. So, she reached out to the community with cycles. “Their parents were worried for the girls’ safety because the school was 20 km away from their homes,” she explains. Another project of hers, Nari Nitti’, is an endeavour to help victims of domestic violence in remote rural villages of Uttar Pradesh. By helping them with vegetable carts, resources to start their papad (Indina snack) businesses and more, Neeti is ensuring them quiet dignity.

Through her initiatives Neeti is ensuring a better life for the people in the Sundarbans who are constantly gripped by the fear of their livelihoods vanishing overnight

Through her initiatives Neeti is ensuring a better life for the people in the Sundarbans who are constantly gripped by the fear of their livelihoods vanishing overnight

Her favourite story to tell is that of Shabana from Sagar village in Madhya Pradesh. Shabana used to drive a cycle rickshaw to support her family until her alcoholic husband sold it one day to get some money to buy alcohol. For the next few days, the family went hungry until a local volunteer got in touch with Neeti and her team. “Instead of buying her a rickshaw, we bought her an e-rickshaw that she could code-share with other women, thus helping them all to earn,” Neeti explains the brilliant idea. Today, Shabana is self-dependent.

Neeti Goel has spearheaded numerous initiatives in Uttar Pradesh wherein she champions women empowerment

Neeti Goel has spearheaded numerous initiatives in Uttar Pradesh wherein she champions women empowerment

At the core of what she does is Neeti’s attempt at giving women back their agency. She’s always maintained, “Women don’t need to be empowered, they are already empowered. They just need opportunity.”

Edited by Khushi Arora

Sources

News